Detail of Wrought Iron Balcony, Third Floor N.E. Elevation; First Skyscraper, 638 Royal Street, New Orleans, Orleans Parish, LA HABS LA,36 - NEWOR,10 - (sheet 19 of 20) Drawing by David Geier, 1935 Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

In partnership with the New Orleans Public Library and the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.

Funding for this Rebirth grant has been provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and administered by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities (LEH) as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act economic stabilization plan.

The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of either the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

In Artistry in Iron: Blacksmiths of New Orleans, we aim to capture the sources and inspiration behind wrought iron designs in New Orleans and the world of the blacksmiths of color who created them. Regularly referred to as craftspeople or artisans, their hard-earned skills and interpretation of historical and cross-cultural symbolism should be recognized for their outstanding artistic contribution to our city’s landscape. Whether enslaved or free, born in Africa, Haiti, or Louisiana, these blacksmiths translated techniques learned from elder family or community members, apprenticeships with master craftsmen, and even their enslavers into symbols of resistance and tributes to their ancestors. Some were compensated for their work; many were not. Nevertheless, blacksmiths comprised a respected group within their communities and a highly valued labor source for their enslavers.

Most historians of ironwork have insufficiently recognized the significance of African metalworking traditions and symbolism as integral to New Orleans ironwork. Taking a closer look at the work and working conditions of enslaved and free blacksmiths of color will inspire a greater appreciation of their contributions to the material landscape of New Orleans’ most historic neighborhoods.

One exception, without which this exhibition would not have been possible, is the work of Marcus Bruce Christian (1900-1976), Black scholar, poet, and head of the “Colored Project” of the Louisiana Federal Writers Project. His 1972 Negro Ironworkers of Louisiana, 1718-1900 is an in-depth study of judicial records, diaries, and countless other primary and secondary sources that presents not only demographic data but explores the relationships between various groups of laborers and skilled craftspeople.

Examining the local built environment—materials, methods, and symbols—has the power to connect our community to its past and helps us prepare for the future. We hope you leave inspired and with a new appreciation for our city’s blacksmiths of color.

Unknown photographer. Marcus Christian, n.d. Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

Unknown photographer. 519 Burgundy Street, c. 1964. Vieux Carré Virtual Library, https://vieuxcarre.nola.gov/. Until at least 1859, it was a blacksmith shop owned by John McDonough.

FROM AFRICA TO LOUISIANA

Beginning in the eighteenth century, the population of New Orleans blacksmiths shifted from a small group of French and Spanish colonists working on behalf of European kings to enslaved African ironworkers who brought skills honed over centuries in their native countries. Eventually, a large number of Louisiana-born free men of color would be apprenticed through indenture to learn the art and trade of the blacksmith for the first time. In the mid-19th century waves of white German and Irish ironworkers competed with the majority Black labor force.

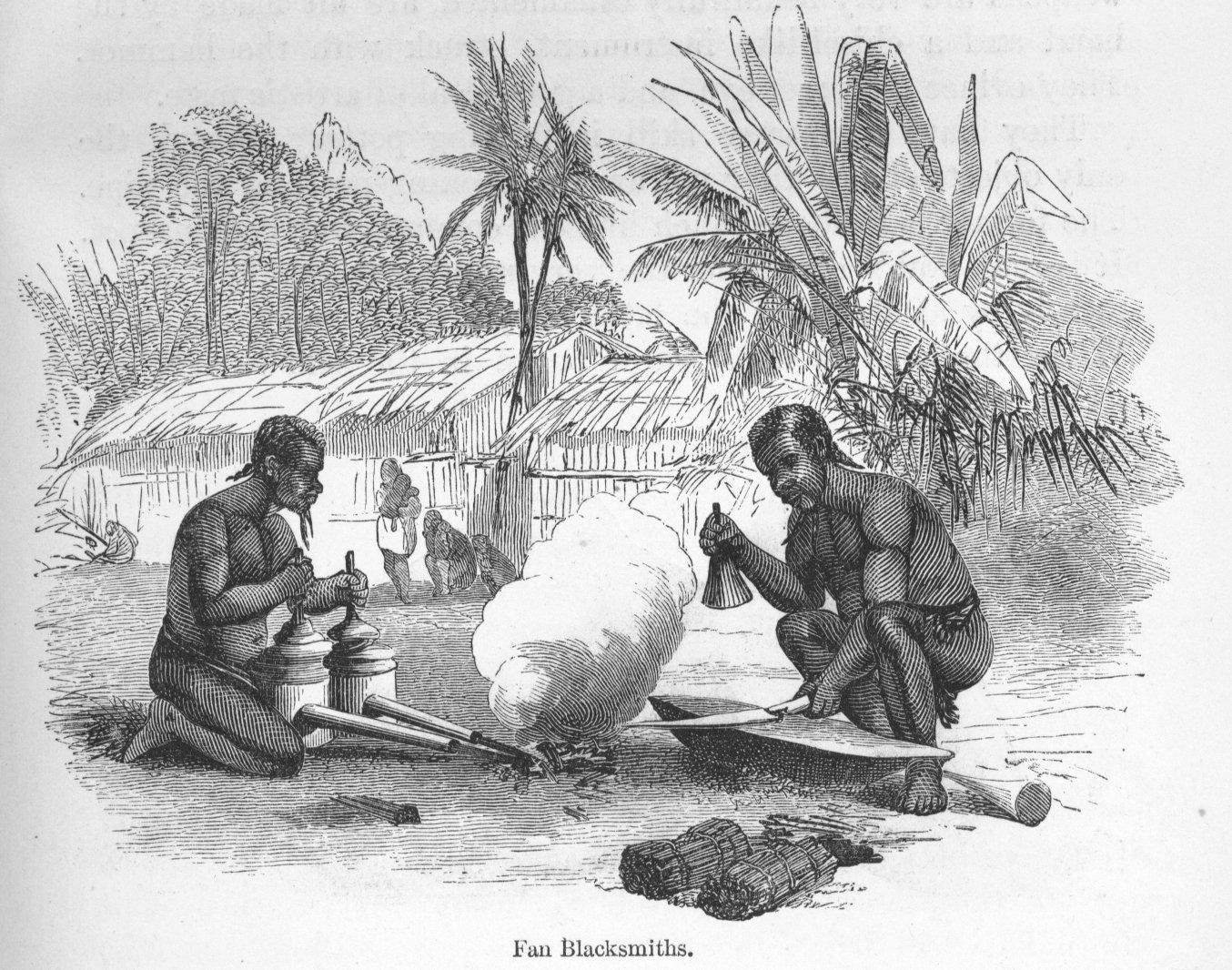

Fãn Blacksmiths, from Paul B. Du Chaillu, Explorations & adventures in Equatorial Africa (London: John Murray, 1861), p. 91. Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed August 4, 2021, http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/1699.

A long history of ironworking was present in Africa before the transatlantic slave trade brought millions of enslaved Africans, including blacksmiths, to North America. As early as the fifteenth century, the Portuguese realized for themselves how valued the blacksmiths’ art was when they arrived at the mouth of the Congo River to learn that the Kongo king was a member of an exclusive blacksmiths’ guild. Some of the extant printed accounting of early ironworking in Africa comes in the form of European diaries. Scientist and missionary David Livingstone’s 1854 notes on Angola’s Golungo Alto District describe a village of around 25,000 households, and, of those, 980 were smiths. In 1850, in all of Louisiana, amongst its population of over 517,000, the census included 989 blacksmiths, only nine more than in the small area recorded in Africa.

Almost all the enslaved people brought to Louisiana under French rule came directly from Africa—primarily from Senegambia, the Bight of Benin, and West-Central Africa—and arrived between 1719 and 1731. After the founding of New Orleans in 1718, building the city required a substantial amount of labor, and the Europeans did not have the necessary skills to do it themselves. Europeans knew Africans possessed certain skills and technological knowledge before forcibly taking them to the New World, and by 1731, Africans outnumbered whites in Louisiana by more than two to one. As historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall and others have argued, the profound impact of several Western African cultures “was more than a simple result of numbers.”

Today blacksmithing remains very much a part of the lives of African peoples living across the continent, especially in the sub-Saharan region, as evidenced by the wealth of material presented in the recent Fowler Museum at UCLA exhibition and publication Striking Iron: The Art of African Blacksmiths.

Exterior View of the Cabildo c. 1938. Johnston, Frances Benjamin (1864 - 1952), photographer. Louisiana State Museum, 1981.132.025.

Forging: The Blacksmith’s Tools Narrated by lead curator Tom Joyce (2:40 min.)

Photograph by Tom Joyce, Yohohou, Togo, 2008, © Tom Joyce; video by Peter Kirby © Fowler Museum at UCLA; video by Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, Kunima, Burkina Faso, 2012, and Indieli-Na and Konko, Mali, 2011, © Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, courtesy of Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium; excerpt from Dokwaza: Last of the African Iron Masters, 1988, video by D. Paul Morris, Nicholas David, and Yves Le Bleis, courtesy of Nicholas David; excerpt from Black Hephaistos: Exploring Culture and Science in African Iron Working, 1995, video by Nicholas David, courtesy of Nicholas David.

SKILLED LABOR, FREE AND UNFREE

Tens of thousands of free people of color, many of them artists and craftspeople, fled revolutions in Haiti and Cuba between 1791 and 1809. They came to New Orleans and cities along the East Coast like Charleston, Savannah, and Philadelphia. After the destruction caused by large fires in 1788 and 1794, New Orleans’s urban landscape benefited from this influx of craftspeople skilled at the building arts.

Enslaved men worked as blacksmiths from their teen years to upwards of 40 years old, as evidenced in the hundreds of “runaway slave” advertisements, sale documents, and indenture records. Some first-person accounts reveal the various duties of blacksmiths; Gilbert Hunt, an enslaved blacksmith from Richmond, Virginia, described working for 18 months for the army “at my master’s shop” during the War of 1812. They “had four forges going constantly;” he “ironed off carriages for the cannon,” made pickaxes, and shoed horses for the army. During this time, Hunt says, “my master gave me complete control of the whole shop.” Marcus Christian and others have documented New Orleans blacksmiths who had enslaved men working in their shops. These included Jean Baptiste Wiltz, whose workshop was on Toulouse Street; at the time of his death in 1817, listed amongst his property were five enslaved people, including an eighteen-year-old male, “somewhat of a blacksmith,” and a 45- or 50-year-old man described as a “complete blacksmith.”

Front entrance, detail of iron work door, The Cabildo, 711 Chartres Street, New Orleans, Orleans Parish, LA (HABS LA,36-NEWOR,4-), July 1934 Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Training of free blacksmiths of color often occurred through the indenture system. Extant records held in the City Archives and analyzed by Paul Lachance reveal the common practice of free people of color sponsoring their teenaged sons as apprentices to local white blacksmiths. Indenture contracts specified terms, typically three years, and according to Louisiana’s 1806 Law on Indentures, a young male’s contract had to expire before he turned 21, unless they decided of their own will (no longer needing a parent or guardian’s permission) to continue the contract for up to seven years. In a contract from January 13, 1824, Jean Baptiste Clavet, about fifteen, “put and bound himself apprentice to Nicholas Murray…to learn the art & trade of black smith.” Between 1816 and 1824, at least six young men of color, from ages 12 to 18, had indenture contracts with Murray. They included Emile, Pierre Bricou, Jean Baptiste Clavet, Julien Jenkins, François Julien, and Joseph St. Amand. In each case, one of the boys’ parents, a free person of color, sponsored them. By 1838 an indentured apprentice from Germany, William Fergner, also worked for Murray.

It was common for New Orleans blacksmiths to provide a variety of metalworking services, including shoeing horses, and forging and repairing tools, wheels, or even weapons. Many blacksmiths came as part of the port city’s extensive maritime trade. For example, in the 1832 directory, Marcellino Hernandez, the Spanish blacksmith who is credited with the iron railings at the Cabildo, is listed as a shipwright, working in ship construction and repair.

Indenture of Jean Baptiste Claver with Nicholas Murray sponsored by Pierre Claver, Volume 4, Number 59, 1824 January 13, page 1. New Orleans (La.) Office of the Mayor. Indentures, 1809 - 1843. City Archives and Special Collections New Orleans Public Library.

Advertisement, True American, August 14, 1838, p. 2 col. 2. Louisiana State University Libraries, Special Collections (http://www.lib.lsu.edu/special)

BLACKSMITH’S SHOPS & TOOLS

No matter where in the world they are working, blacksmiths require iron, a forge on which to heat and work the iron, fuel to achieve high temperatures, and a few tools, including at minimum a hammer, anvil, tongs, and bellows. When enslaved blacksmith Gilbert Hunt of Richmond, Virginia, visited Africa in the early 19th century, he watched a local blacksmith at work, “sitting down on the sand, his legs crossed…his anvil, bellows, hammers &c., all around him. Even in this position, he could beat me working on all pieces.” Almost 200 years later and across continents, blacksmith tool design has changed very little. In his fully illustrated handbook Museum of Early American Tools (1964, below), Eric Sloane points out that “hardly an implement or utensil cannot be traced to the early blacksmiths.”

In a rural Louisiana setting, in the 18th and 19th centuries, a large plantation typically had a kiln, a forge, and carpenter shop; the blacksmiths employed there, whether enslaved or free, were responsible for making most if not all the tools, horseshoes, locks, and hardware on site. While enslavers considered the field laborers easily replaceable, the skills of the one blacksmith and two engineers made them the most valuable among the more than 200 enslaved people at Valcour Aime’s Le Petit Versailles plantation in Louisiana.

Present-day 519 Burgundy Street, formerly a blacksmith shop. Plan Book 35, Plan 56. 1859 Feb. 15. Charles De Armas, engineer. Courtesy Hon. Chelsey Richard Napoleon, Clerk of Civil District Court, Parish of Orleans

In cities like New Orleans, before large iron foundries took their place in the late-19th century, blacksmiths’ shops were spread out every few blocks, and any building or mode of transportation relied on their production. Whether shoeing horses, turning wheels, or making hardware for shutters, doors, and locks, blacksmiths were essential to the daily function of urban life. In 1859 Charles deArmas recorded the plan and elevation of one such shop at present-day 519 Burgundy Street, property of the late John McDonough (above). On the plan the building is identified as a blacksmith’s shop, and tools are visible through the doorway. We get another glimpse inside a mid-19th century blacksmith shop in an 1864 sketch by A.R. Waud (right). Large bellows point towards the forge; a hammer and anvil sit in the middle of the room; a wooden stand holds numerous ironworking tools; and horseshoes hang on the wall and clutter the floor.

Drawing of tools: Eric Sloane, “The Blacksmith,” from A Museum of Early American Tools, 1964. With permission from the Eric Sloane Estate.

Alfred Rudolph Waud, (1828 - 1891), draftsman. Blacksmith Shop, 1864.Pencil, ink, and Chinesewhite. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1977.137.2.39.

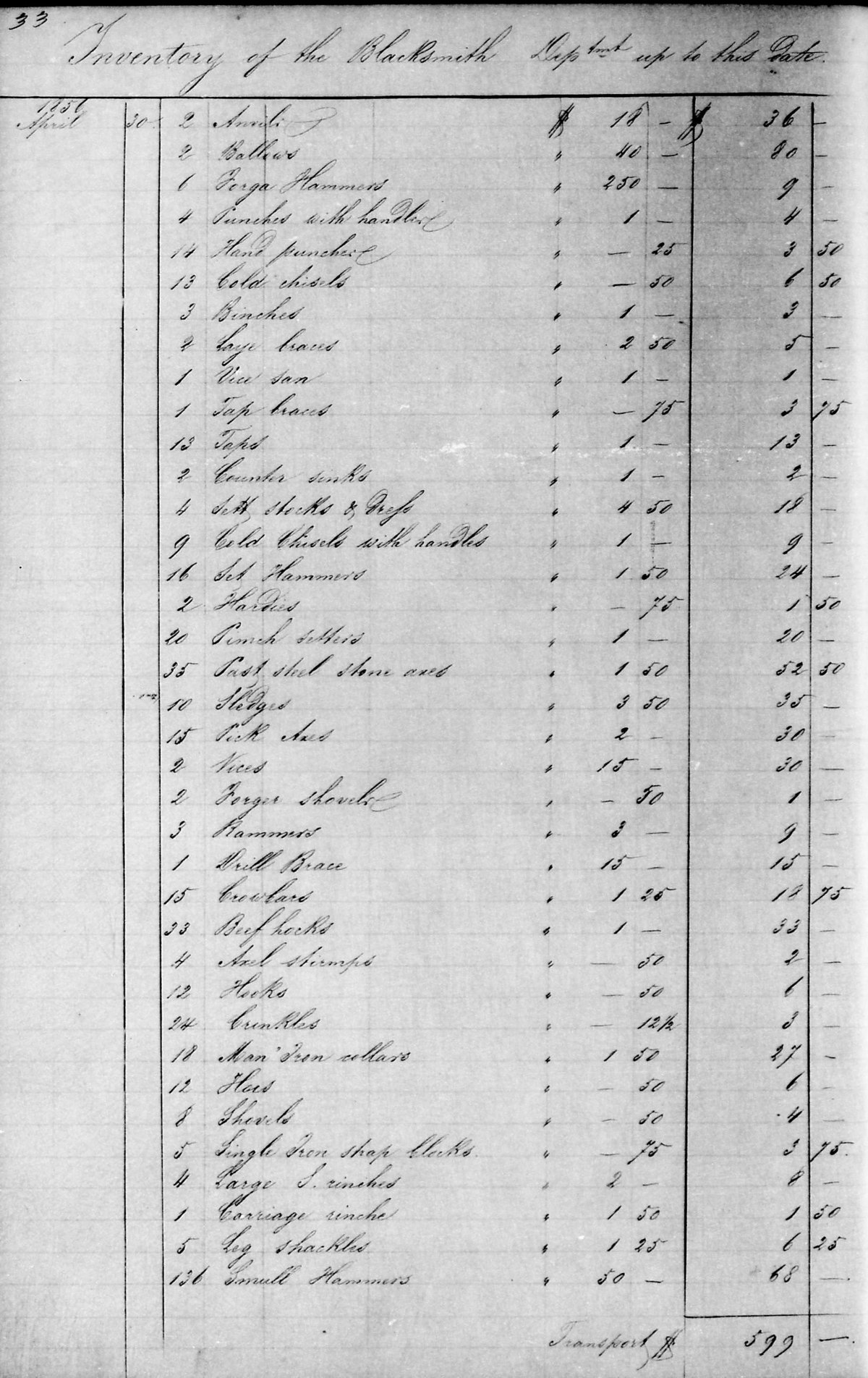

“Blacksmith tools, Jan. 1852, from Inventories of stock on hand, 1851-1856. New Orleans (La.) Workhouse. Records, 1851-1857. City Archives and Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library.”

Analyzing the names and addresses of blacksmiths in the 1822 and 1832 New Orleans City Directories one finds, as expected, the French names almost exclusively located on French-sounding streets, in the present-day French Quarter, Marigny, and Seventh Ward; and conversely, the Anglo names located across Canal in the present-day Central Business District and Warehouse District. In 1836, for fifteen years, the city would be officially divided into three municipalities. Before and after this period, there were de facto demographic designations. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and even today, the Seventh Ward continues to be a center of Black enterprise and a place where talented practitioners of the building arts pass their knowledge on to future generations.

New Orleans blacksmith Darryl Reeves hand-forging a tool at the Beauregard-Keyes House "The Built Environment of New Orleans" program, Summer 2021.

“ARISTOCRATS AMONG SLAVES”

In Louisiana, enslavers and those employed in the slave trade valued African-born blacksmiths more than most other laborers, skilled or unskilled. As Marcus Christian writes, “Each plantation had its kiln, its forge, and its carpenter shop. Of the three, the forge, with its blacksmith, came nearest to being the cornerstone of the plantation, for blacksmiths were aristocrats among slaves during the Spanish and American periods.” During the French period, in 1748, Joseph Dubreuil, contractor of the king’s works and enslaver of 500 people, complained to the Superior Council after three of them were arrested for theft. He argued that the arrests forced him to close his sawmill and blacksmith shop, and to suspend his cabinetmaking. Evidently, Dubreuil highly valued the African blacksmith and carpenter; he insisted on their innocence and demanded they be returned immediately.

In the 1840s a purchaser might pay upwards of $1500 for an enslaved blacksmith, but the price for an unskilled laborer ranged from around $400 to 800. Also, bondsmen could hire themselves out, and their valuable skills meant they could bring back more money to their enslaver and earn some money to put towards their freedom.

Runaway slave advertisements in New Orleans newspapers offered rewards for self-emancipated blacksmiths. They included a $250 reward in 1846 for “a Black man called Emanuel, blacksmith by trade”; in 1828 a $100 reward for Sam, “aged about 30 years…well built…a good blacksmith.” Slave sale documents also provide some insight into the value placed on the skills of these bondsmen. Benjamin Powell of New Orleans sold a 22-year-old “rough blacksmith” named William to Henry E. Sule of East Baton Rouge for $950 in 1851; J.B. Scudder of East Baton Rouge Parish paid C.H.P. Marr $1300 cash for the blacksmith Jerry, also 22, in 1846.

Since iron was the most effective material to restrict the movement of prisoners and enslaved people, blacksmiths employed their skills to create tools of suppression—shackles, handcuffs, collars, and jail bars—whether they liked it or not. Enslaved blacksmith Gilbert Hunt, after helping save prisoners from a penitentiary fire in Richmond, Virginia, decried the fact that “the next day I spent making hand-cuffs for the poor fellows.”

Blacksmiths of color also made use of their strengths and perceived value to resist oppressive forces and become leaders in their communities. They were among the artisans who figured prominently in several 18th- and 19th-century rebellions.

In New Orleans pay for free blacksmiths depended on their skill level and the variety of jobs they could handle in their shops, while indentured apprentice blacksmiths had their training, medical needs, food, drink, room, and board provided for as part of their contract.

Inventory of the Blacksmith Department from Inventories of stock on hand, 1851-1856. New Orleans (La.) Workhouse. Records, 1851-1857. City Archives and Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library.

St. Louis Cemetery I, Dubreuil Tomb, side section with fence, 1968-1974. Betsy Swanson (b. 1938), photographer. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1978.144.417.

SPIRITUALITY AND SYMBOLISM

Often overlooked by scholars of American art and architectural history, African symbolism permeates the fabric of 18th- and 19th-century buildings in the French Quarter and elsewhere. In addition to the plentiful cast iron balconies and galleries for which the city is known, innumerable forged iron hinges, hooks, locks, latches, tools, and cemetery fences hold hidden histories of artistry, spirituality, and resistance.

Central spire, St. Louis Cathedral, New Orleans. Photo by Katie Burlison, 2021.

As historian of African art Henry Drewal reminds us, in Africa, not only are the blacksmith’s artistic creations significant, but the fact that they also forge the tools that are used to create their art makes them even more powerful: “Iron is…an activator of spiritual power…The smith is master of the transformative process of making iron from the earth into culture’s tools…He fashions the tools of creation. Over a lifetime of use, the blacksmith’s tools come to possess the life force or ‘performative power’ of the maker himself.”

After two great fires in 1788 and 1794 destroyed over seventy percent of New Orleans’s structures, two-story townhouses replaced many of the old single-story cottages. This development allowed for the introduction of iron balcony and gallery railings whose blending of African, French, and Spanish designs created a new streetscape that largely remains in today’s Vieux Carré.

The rebuilding of New Orleans coincided with the influx of free people of color artisans and enslaved Africans from revolutionary Haiti. From Africa to Haiti to New Orleans, they brought with them values and religious symbolism: Ogun, the Yoruba patron saint of iron, became Ogou. The importance of circular motifs (widely representing the regeneration of life), adinkra symbols from the Gold Coast (Ghana), and Haitian vévés (sacred, ritual paintings in Vodun) carried over into the work of the city’s blacksmiths of color. Blacksmiths and other craftspeople incorporated West African adinkra symbols into their forged and carved creations, imbuing them with hidden meanings that their fellow Africans in Louisiana would recognize.

Ancestors and ancestral memories were a daily focus of Africans and people of African descent during enslavement. Oral traditions within the community ensured a secret, coded, and empowering mode of resistance. Ironwork was a means through which enslaved and free African communities of New Orleans connected with Africa.

The adinkra symbols and their associated messages (below) have permeated many areas of art and design across the globe. More research is needed to tell us exactly whose hands touched the pieces of ironwork throughout New Orleans, but the presence of these African symbols is undeniable.

Asase ye duru (“the earth has weight”) signifies divinity of Mother Earth

Dwannimmen (“ram’s horns”) signifies humility and strength

Sankofa (“return and get it”) signifies learning from the past

CARRYING THE TORCH

By the 1850s cast iron was in general use in New Orleans; elaborate floral, vegetal, and geometric patterns embellished the railings, galleries, and gates of two- and three-story buildings throughout the French Quarter and the new “American Sector” across Canal Street. Beginning in 1825 with the establishment of the Leeds Iron Foundry, the number of individual blacksmiths shops in the city declined, while those of larger industrial foundries grew. The benefits of cast iron included speed of production and a wide variety of readily available patterns, offered in catalog form and imported domestically and internationally; however, with the rise of cast iron the distinguishing characteristics of individual craftsmen declined. Today, a gate or railing may comprise wrought iron upright elements with cast finials from pre-existing patterns. But for Darryl Reeves, a “restoration blacksmith” specializing in repairing and reproducing the work of 18th- and 19th-century iron workers, it is important to use as much of the original material as possible. At his shop in New Orleans’s Seventh Ward, Reeves hand forges elaborate gates, railings, and more recently, furniture, that faithfully follow or draw creative inspiration from historical designs he has come in contact with during his decades-long career.

Blacksmith Darryl Reeves at Xiques House, Dauphine Street, New Orleans. Courtesy Jonn Hankins/New Orleans Master Crafts Guild.

Blacksmith Darryl Reeves forges an iron tool at the Beauregard-Keyes House, 2021. Photo by Katie Burlison.

Reeves and other master craftspeople are passing their skills and knowledge down to the next generation through the New Orleans Master Crafts Guild. In addition to hands-on training, research initiatives—including archival databases and scholarly publications—community workshops, live demonstrations, and walking tours are helping to raise public awareness of the under-represented contributions of blacksmiths, carpenters, architects and builders of color throughout New Orleans and beyond.

Apprentice Brandon Smith working on the iron fence at Jackson Square. Courtesy Jonn Hankins/New Orleans Master Crafts Guild.

Related projects, databases, and institutions to explore:

New Orleans Master Crafts Guild:

http://neworleanscraftsmen.org/

Louisiana Digital Library:

https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/

Marcus Christian Collection, University of New Orleans Earl K. Long Library:

Digitized manuscripts: https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/uno-p15140coll42%3Acollection

Finding aid: https://libguides.uno.edu/mss011

Ashé Cultural Arts Center:

https://www.ashenola.org/

Le Musee de FPC:

https://www.lemuseedefpc.com/

New Orleans African American Museum:

https://www.noaam.org/

Afro-Louisiana History and Genealogy database:

https://www.ibiblio.org/laslave/

Black Craftspeople Digital Archive:

https://blackcraftspeople.org/

Materializing Race:

https://www.materializingrace.com/

Freedom on the Move:

https://freedomonthemove.org/

Fowler Museum at UCLA:

https://fowler.ucla.edu/exhibitions/striking-iron/