Throughout New Orleans’ tumultuous 19th century women were essential in preserving and reinforcing white Creole culture. Wealthy white Creoles were the descendants of French and Spanish colonists who, influenced by and dependent on Native Americans and free and enslaved people of color, had controlled the Lower Mississippi Valley since the 17th century. With the influx of Anglo immigrants after the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, white Creoles sought to bolster their identity and separate themselves from this new, white population by emphasizing their continental European origins and distinct culture. Creole mothers performed much of this cultural labor in rearing Catholic francophones deft at navigating New Orleans’ unique racial, ethnic, and classed landscape.

Upper-class, white Creole women chose religious or domestic life; these were their reputable options. Adelaide Grima, like most women, chose to marry and bear children. Rearing children in the cholera and yellow fever rampant days of 19th-century New Orleans was only one of a mother’s worries. Responsible for the physical and spiritual health, happiness, and tranquility of their home and household, Creole matriarchs ruled the domestic sphere. While enslaved and free women of color performed, or assisted in, the day-to-day childcare, cooking, and cleaning, Creole mothers managed free and enslaved workers, kept household accounts and schedules, maintained their family’s social status through their children’s marriages and daily visitations, and counseled their husbands and sons. During the Civil War, these matriarchs adopted new responsibilities traditionally performed by men or enslaved people, like political activism and domestic labor. While the Reconstruction era ushered in the decline of white Creole culture, the influence of Creole matriarchs is still perceptible in New Orleans today.

With the return of Mme. Felix Grima, née Marie Sophie Adelaïde Montegut, 1852, by Antonio Martí, to Hermann-Grima Historic House, we examine some of the roles, strictures, and liberties of Creole matriarchs.

Antonio Martí

Barcelona, b. 1813

Mme. Felix Grima, née Marie Sophie Adelaïde Montegut, 1852

Oil on canvas

Museum purchase, 2018.001

Adelaïde Montegut Grima

Adelaïde Montegut Grima (1811-1876) was born into a wealthy family who had been in colonial New Orleans for two generations. In 1831 she married Judge Felix Grima, also a New Orleans native. The museum recently acquired this portrait of Adelaïde by Spanish artist Antoni Marti in 1852, painted at least a decade after another portrait of her in the Hermann-Grima + Gallier Historic Houses collection. Between 1835 and 1856 Mme. Grima bore nine children, five of whose portraits are represented in this exhibition. As evidenced in a surviving collection of Civil War-era family letters, she cared deeply for her six sons and three daughters. In them she writes her children, particularly her sons who are away from home, to strengthen their morale, and remind them of the support their belief in God could provide.

In 1864, Felix, Adelaïde, their two youngest sons George and Edgar, and their three daughters, Louise, Marie, and Adelaïde, left New Orleans for Augusta, Georgia, where they remained for the remainder of the Civil War. Adelaïde writes often to three of her other sons: Alfred and Paul, Confederate soldiers; and Victor, studying medicine in Paris. It is not only the dangers of war to her sons and her extended family that worry her, but the conditions in which they are living in Augusta are far from comparable to their New Orleans mansion: “a small house with four rooms…would have been much more advantageous…your father is still sleeping on a mattress on the floor. Louise and Marie would be very happy if we could be at our house.”

Unknown

George, Adelaide, and Edgar Grima, n.d. (original, 1856-1860)

calotype copy of a lost original

Gift of Alfred Grima Johnson, 1996.4.21

Unknown

Marie and Louise Grima, n.d. (original, c. 1855)

calotype copy of a lost original

Gift of Alfred Grima Johnson, 1996.4.20

Unknown

Adelaïde Grima, n.d. (original, c. 1860-65)

calotype copy of a lost original

Gift of Alfred Grima Johnson, 1996.4.18

In a July 1872 letter Felix writes to Adelaïde in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, that their youngest child, Adelaïde, has finally finished at the “pension Marie LePeine”—likely referring to a girls’ boarding school where French was the preferred language. Paul Grima, writing while fighting for the Confederacy in Virginia, advised in 1864 that “my sisters [Louise, Marie, and Adelaïde] should…extend their knowledge of the English language, against which our Creole women have always had a distaste.” An advertisement for a Young Ladies’ Academy in an 1855 Daily Picayune boasts that every subjects is taught in “both languages.”

Unknown

Edgar Grima, n.d. (original, c. 1848)

calotype copy of a lost original

Gift of Alfred Grima Johnson, 1996.4.16

Unknown

Marie Grima, n.d. (original, c. 1858)

calotype copy of a lost original

Gift of Alfred Grima Johnson, 1996.4.17

Unknown

Louise Grima, n.d. (original, c. 1860)

calotype copy of a lost original

Gift of Alfred Grima Johnson, 1996.4.19

Enslaved Mothers and Family Life

Of the women known to be enslaved by the Grimas, none were identified as a child nurse, but enslaved or free women of color may have assisted Adelaïde in caring for her nine children.

The engraving below shows two women and a child of color, the central woman strolling what may have been the child of her enslaver.

Juggling the needs of their own children, enslaved mothers reared their enslavers’; children from infancy through adulthood, and generational enslavement was not uncommon. Children born of enslaved women also were enslaved and could be sold away from their families as young as age ten.

At least seven enslaved families lived and worked for the Grimas between 1840 and 1865. Sophie, enslaved by Adelaïde’s mother-in-law, Marie Anne Filiosa Grima, was emancipated between 1838 and 1840. While Sophie became employed by the Grimas, her three children--Charles, Agathe and Marie--remained enslaved on the property. Three of Agathe’s four children--Henry, Felicie and Eugène--were emancipated in adulthood by Felix Grima. The last record of her daughter Amelie is a death certificate stating that she died in the Grima home in 1851.

While it is impossible to confirm the number of matriarchs enslaved by the Grimas, due to the illegality of literacy for the enslaved, below are those of whom the Hermann- Grima + Gallier Historic Houses have a record: Sophie and her children Agathe, Charles and Marie; Agathe and her children Eugène, Félicie, Amelie and Henry Beaurepaire; Suzanne and her children Anaïs, Odile, Angela, Henry, Pauline and Albert; Jane and her unnamed child; Mathilde, pregnant, and her children Marguerite, George, Clara and Virginia; Sally and her son, George; Justine, her daughter, Emma, and an unnamed infant; Mary Ann Butler and her unnamed baby.

Samuel Smith Kilburn

Boston, 1831-1903

Lafayette Square, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1859

engraving

Museum purchase, 1973.53.9

Catholicism

Catholicism was central to the lives of Creole families in 19th-century New Orleans, dictating how they mourned, celebrated holidays, and educated their children. The 18th-century Code Noir (Black Code) even required that enslaved people be baptized in the Catholic Church. According to baptismal records of the St. Louis Cathedral, Felix Grima and his sister Françoise served as godparents to Henry Beaurepaire, a child their family enslaved. Virginie Hermann and the four Gallier daughters attended the school at the Ursuline Convent, where their parents had married.

Crucifix, c. 1850

rosewood, brass

Museum purchase, 1974.15.1a-b

Written by Virginie Hermann’s first husband, Dr. Joseph Ursin Landreaux (1808-1852), this journal begins with personal anecdotes and describes their 1835 nuptials at her family home as well as the birth of their four children. As a doctor, Landreaux paid particular attention to medical events, like Virginie’s labor, writing, “On Wednesday, 25 January 1837, at 2:45 a.m., after three hours of labor, my wife brought into the world a son [Robert]…Mme. Frémaux was absent; it was Mme. Giguel the midwife who delivered my son.” Robert was the second of their four children Virginie would have in as many years. Quick succession of births was the norm in 19th-century Creole families; if a woman did not enter the convent, motherhood was seen as the essential alternative.

Journal, 1835-1932

On long term loan from the Van Horn family, L2007.1.3

A mother’s duties in 19th-century Creole New Orleans households were wide-ranging. If her family enslaved people, her tasks would include fewer responsibilities such as cooking and cleaning, washing, and ironing; however, in many upper-class Creole households, mothers instructed their own children in etiquette, reading and writing. Such books as this one by “Miss Leslie,” which was advertised for sale in New Orleans newspapers, promoted “encouraging [girls] in the love for books; but do not set them at any other branch of education ‘til they are eight...little girls may begin to sew at 4 or 5, but only as an amusement, not as a task.”

Eliza Leslie

1787-1858

born Philadelphia; died Gloucester City, N.J.

The ladies’ guide to true politeness and perfect manners, or Miss Leslie’s behaviour book, a guide and manual for ladies, 1864

Book

Museum purchase, 1974.24

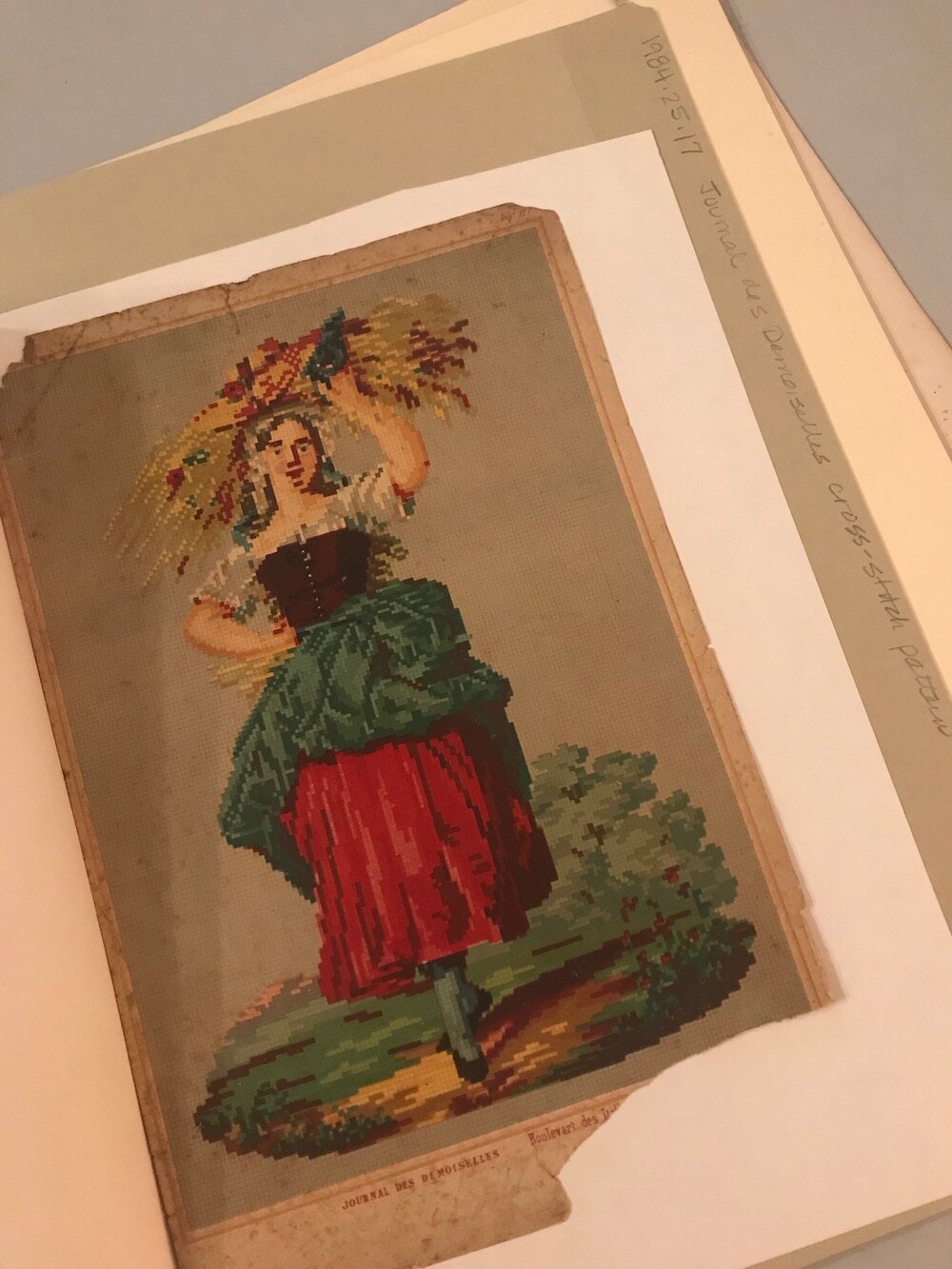

Unknown

Needlework pattern from Journal des Demoiselles, mid-19th century

Paris

paper

Gift of Mrs. Francis T. Morgan, 1984.25.17

Unknown

Reticule, c. 1860

Beads, silk, cotton, metal

Gift of Mrs. Gordon Reese, 1989.14.1

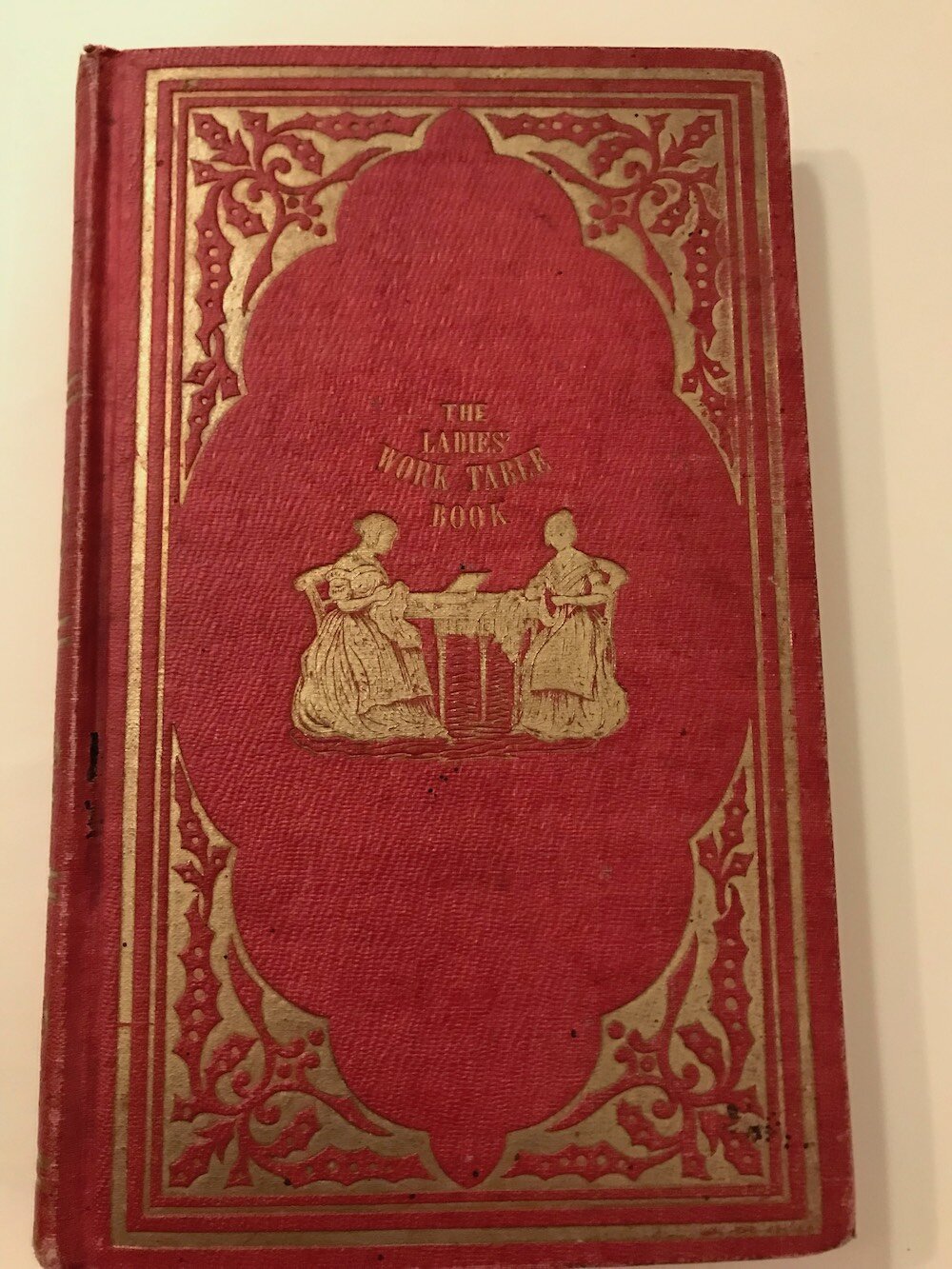

The Ladies’ Work-Table Book

Creole mothers would have been instrumental in teaching their daughters how to sew; it was a skill fundamental to their mastery of the domestic sphere. One of many period books instructing women on needlework, this volume connects a woman’s ability to sew to her satisfaction and usefulness: “Never is beauty and feminine grace so attractive, as when engaged in the honorable discharge of household duties, and domestic cares.” When, in the case of more affluent women, needlework skills were not necessary for fabricating articles for one’s family, they were considered useful to make items “for the aid and comfort of the deserving poor”.

The Ladies’ Work-Table Book; containing clear and practical instructions in plain and fancy needlework, embroidery, knitting, netting, and crochet, 1858

Gift of Mrs. F. Evans Farwell, 1997.1

The Ladies’ Work-Table Book; containing clear and practical instructions in plain and fancy needlework, embroidery, knitting, netting, and crochet, 1858

Gift of Mrs. F. Evans Farwell, 1997.1

The Imitation of Christ

The Imitation of Christ, first printed in Latin in the 15th century, is the mostly widely read devotional work after the Bible and is considered the most important work in Catholic Christianity. A French-speaking Catholic Creole family like the Grimas undoubtedly would have consulted this book on a regular basis. The Hermann, Grima, and Gallier families were members of St. Louis Cathedral.

Unknown

Imitation de Jésus-Christ, 1863

Gift of the Grima family, 1971.11.3

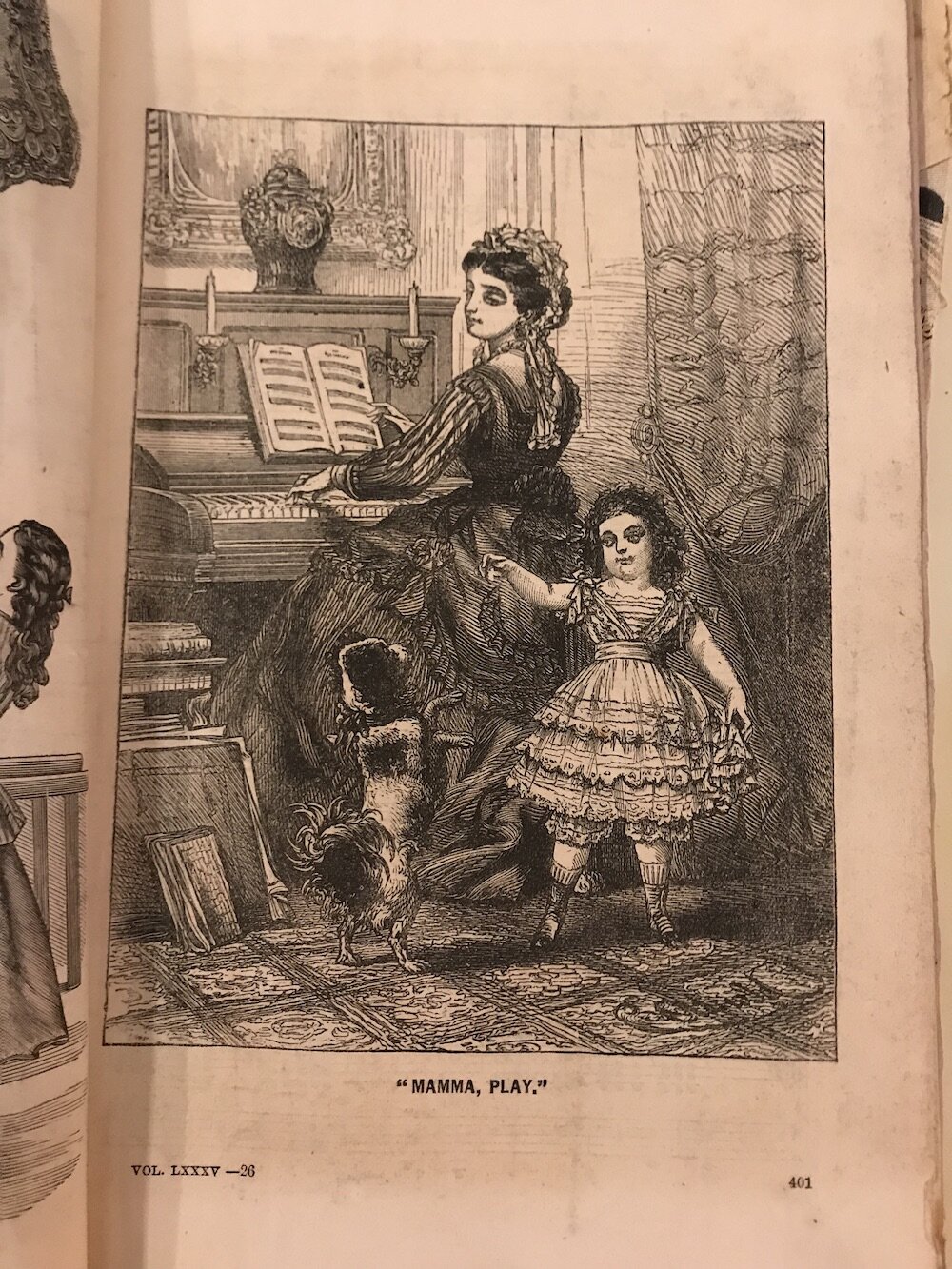

Godey’s Lady’s Book Vol. LXXXV

Between 1825 and 1850, the number of magazines and journals in the United States increased from one hundred to six hundred. Female-centric periodicals, like Godey’s Lady’s Book, manuals of “domestic economy”, guides to politeness, respectability, and cookbooks, instructed women on cooking as well as how to set their tables, clean silver, make candles, and eliminate odors. In addition to needlework patterns and fashion plates, Godey’s offered comedic and romantic literature, and illustrations like this one.

Unknown

Plate from Godey’s Lady’s Book Vol. LXXXV, November 1872

Engraving

Hermann-Grima & Gallier Historic Houses Study Collection

Music

Learning to play music was an integral part of an upper-class Creole woman’s education, and her skill level marked her social status and upbringing. Girls received private instruction from local schools and tutors, but their primary training in instrumental music, singing, and dancing took place at home under the direction of their mother, and sometimes their father. Local music publishers and vendors retailed sheet music for polkas—like this one dedicated to New Orleans native Louis “Moreau” Gottschalk—waltzes, and polonaises for the piano forte. Musical performances in the home provided opportunities for a young woman to display her talents, be courted by young men, and entertain her family and their guests.

Giacomo Meyerbeer, composer

1791-1864

Born Berlin; died Paris

L’Etoile du Nord/The Star of the North Grande Polka pour le Piano, 1854

Sheet music

Gift of Charles L. Mackie, 1989.10.1