H. Tardy Hart, Bourbon Street, 601 block, New Orleans, LA. French Opera, interior, ca. 1918, Ink and watercolor on paper, Louisiana Drawings, Southeastern Architectural Archive, Tulane University Special Collections

Heart of the old French Quarter

Recognized by many architectural historians and preservationists as one of the most important buildings in New Orleans history, the French Opera House towered over the corner of Toulouse and Bourbon Streets for sixty years and withstood some of the most impactful events the city has ever witnessed. Completed in November 1859, less than two years before the start of the Civil War, the “new” French Opera House stood as one of the last symbols of a Creole society that had been present in New Orleans for more than a century.

For its design and construction, the New Orleans Opera House Company—formed just a month before the project’s groundbreaking—employed the top local architects, builders, and craftsmen of their day. What resulted was by all accounts an elegant, commodious structure both inside and out.

For many, the opera in the late nineteenth century provided a welcome escape from the disease-ridden city, seemingly in constant mourning for victims of yellow fever and cholera, and a place where a diverse group of citizens (and before the Civil War, enslaved people) could enjoy a performance in the same building, if not in the same tier. When it burned one hundred years ago, Lyle Saxon, wrote in Fabulous New Orleans that “The heart of the old French Quarter has stopped beating.”

Marie Adrien Persac (ca. 1823-1873), delineator, French Opera House, 1859-1873, Watercolor on paper, The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1939.5

A Temple of Song

New Orleans was the first American city to offer opera as entertainment. In 1796, the Théâtre St. Pierre, staged the city’s first documented opera, André Ernest Grétry’s Sylvain. The Théâtre Saint-Philippe opened in 1808, and the Théâtre d’Orléans in October 1815, after being delayed because of the Battle of New Orleans. Under the leadership of Saint-Domingue native John Davis and his son Pierre, the Orléans remained the city’s most important venue for concerts, operas, and balls until the 1850s. In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, theaters featuring English-language productions opened: James Caldwell’s Camp Street Theatre, the New American Theatre, and the Saint Charles Theatre, which, when it opened in 1835, was the largest hall in the nation.

New Orleans-born impresario and husband of soprano Julie Calvé, Charles Boudousquié succeeded Pierre Davis as director of the Théâtre d’Orléans in 1853. In 1858 Henry Parlange purchased the Théâtre d’Orléans from the estate of businessman and philanthropist John McDonough. When Boudousquié and Parlange were unable to come to terms on the building’s lease, some of the opera’s oldest and wealthiest supporters formed the New Orleans Opera House Company and set out to erect a new building. As The Sunday Delta of December 4, 1859 declared, this “Temple of Song”, the new Opera House, “should combine elegance and simplicity with the greatest degree of comfort possible.”

Soards’ Directory Co., French Opera House Seating Plan, 1890 or 1891, Ink on paper, The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1959.172.6

For more on the decorative materials used, explore the Benson Ledger, available online.

The French Opera House Building

On April 18, 1859, locally renowned architects and builders James Gallier Jr. and George Esterbrook signed a contract with the Opera Company to have the French Opera House building ready by the first of November of the same year. At least one other architect, J.N.B. De Pouilly, had made designs for the Opera House, but completing a project on a grand scale in such a short time frame may have seemed impossible. The projected cost of the building and ground was about $200,000 and furnishings $50,000 more, according to the Daily Crescent, although the building contract had specified a $118,000 price tag. Esterbrook supervised the craftsmen, who included skilled stone masons, brick layers, plasterers, iron founders, slaters, plumbers, coppersmiths, and stair builders.

When the Opera House opened in December 1859, local newspapers described in detail its exterior and interior decoration, and lauded it as “a magnificent monument to [Gallier and Esterbrook’s] ability, taste, and energy.”

Italianate in style, the interior featured an elliptical ceiling that rose 58 feet above the floor of the pit. “Exquisite” ornaments stamped in zinc and gilt decorated the four tiers of galleries for spectators. According to The Sunday Delta’s in-depth tour of the Opera House, manager Charles Boudousquié chose these elements in Paris, and Mr. [Prudent] Mallard installed them. Flanking the stage stood four fluted Corinthian columns; the fillets and moldings of the shafts and bases were gilt, and they rested on pedestals painted and veined to imitate marble. Outside, an expansive gallery protected ladies entering and exiting their carriages in inclement weather.

Seating capacity was 1,600; with packed aisles and halls of standing spectators, the audience could reach up to 2,500. In addition to the pit, four tiers of gallery seats divided patrons by class and race. The first tier, a dress circle, consisted of 52 stalls with four seats each. The second dress circle contained eight open stalls and twenty latticed boxes, each with a small parlor behind it for receiving friends and resting during the entr’acte. The box’s lessee could fit out the parlor as he or she wished, and also had at his or her disposal the advice of in-demand local furniture manufacturer and dealer Prudent Mallard.

Near the first dress-circle seating was the 60-foot-long by 26-foot wide by 28-foot high grand saloon, described in The Sunday Delta’s detailed tour of the building as “lighted and ventilated by two heights of windows, with casement, sash and inside blinds…heated by two fireplaces with marble mantels…[with] two large center flowers…fixed in the ceiling, from which depend two large gas-chandeliers.” There was a Club Room set aside for wealthy patrons who had purchased stock to help build the Opera House.

The third tier, plainly furnished with seats without boxes or divisions, was, according to the Delta’s May 23rd description, “for the cheap admission of white people, and…equal to the pit.” The fourth and highest tier was for people of color. When a writer for the Daily Delta toured the newly opened Opera House, he noted how it was necessary to enter a separate door on the St. Louis Street side and climb “a stair which conducts one in a tortuous course” to access the “colored gallery”. An 1869 law would be the impetus for several lawsuits challenging the racial segregation of the Opera House.

Timeline

“Opera Company director Charles Boudousquié and supporters decide to move out of the Orleans Theater after differences with the property’s new owner, Henry Parlange”

“The Civil War formally begins after Southerners fire at Fort Sumter off Charleston, South Carolina.”

“Architect J.N.B. De Pouilly creates two designs for a new opera house.Image:

Jacques-Nicolas Bussière De Pouilly (1804-1875)

De Pouilly Sketchbook No. 3, 1830-1860

Ink, wash and watercolor

The Historic New Orleans Collection

1979.93

”

“The firm of Gallier & Esterbrook contract with the New Orleans Opera House Company to build new opera house for $118,500, to be completed by November 1 of the same year.”

“The first brick is laid in the foundation, at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse Streets.”

“The French Opera House opens for the first time, with a gala performance of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell.Image:

”

Jeudi, 1er Decembre 1859, ouverture du Theatre de l’Opera…, 1859

Ink on paper

The Historic New Orleans Collection

PN2277.N492 T54 1859

“Eighteen-year old Italian soprano Adelina Patti performs Robert Le Diable, Il Trovatore, and Les Huguenots.”

“Major General Benjamin Butler and 5,000 Union troops occupy the city of New Orleans.”

“Major General Nathaniel Banks replaces Butler as commander of the Department of the Gulf.”

“Mrs. Nathaniel Banks hosts a masked ball, in honor of George Washington’s birthday at the French Opera House.”

“The steamer Evening Star sinks off the coast of Georgia, drowning an entire 52-person French opera troupe traveling to New Orleans for a season-opening performance at the French Opera House.”

“A Louisiana law forbids “discrimination in places of public resort,” and over the next six years, people of color file at least fourteen lawsuits against owners of a variety of establishments. In one such suit, a free Creole of color composer named Eugène-Victor Macarty filed suit against the director of the French Opera House, E. Calabrési, for denying him access to the white seating area. Calabrési argued that his white patrons would be unwilling to sit in the same section as a person of color. The case failed to bring about any immediate resolution, but Creoles of color persisted in their fight for access to integrated seating, even staging a boycott of the Opera in the 1874-1875 season.Image:

”

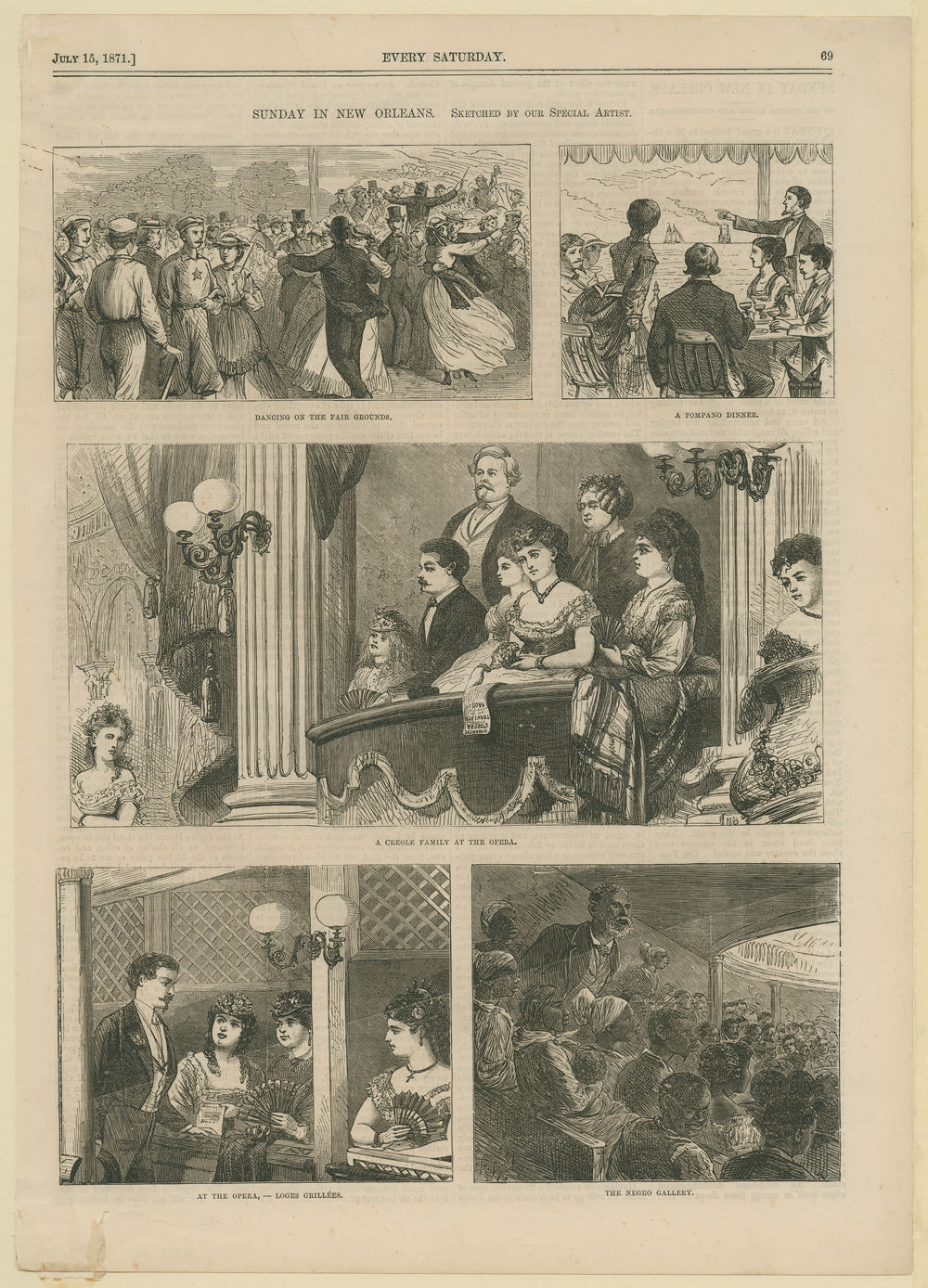

Alfred Rudolph Waud (1828-1891), delineator

Russell Richardson, engraver

Sunday in New Orleans, 1871

Wood engraving

The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise

1953.90 i-iii

“The French Opera House building is put up for sale. The Daily Picayune proclaims that “a property so valuable as this…should by no means be allowed to go out of the hands of the clubs and capitalists of New Orleans. If rented for balls, parties and other entertainments part of the year, it could be leased the balance of the year for operatic and other dramatic purposes and would prove a splendid investment.”

“Mardi Gras krewes Comus, Proteus, Nereus, and others rent out the Opera House for balls.Mistick Krewe of Comus, distributor

Comus Invitation, 1893

Color lithograph

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection

1958.102.23 a,bKrewe of Proteus, distributor

”

Proteus Admit Card, 1893

Color lithograph

The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Fonders Collection

1958.102.47

“The building had fallen into disrepair. Philanthropist W.R. Irby, instrumental in salvaging several French Quarter buildings in the early twentieth century, purchased it and donated it to Tulane University.”

“The Vatican Choirs, comprised of 70 singers from the Sistine Chapel, St. John Lateran, and St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, perform at the French Opera House to a full house.Image:

”

E. V. Richards, Jr., producer

Program for the Vatican Choirs appearing at the French Opera House, 1919

Paper

The Historic New Orleans Collection, Williams Research Center, Seemann Family Papers

MSS 625.5

“The French Opera House is destroyed in an early morning fire.Image:

”

Charles L. Franck, photographer

French Opera House after Fire, December 5, 1919

Photograph

Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection

1979.89.7434

“A “small but determined” group of local business and property owners meet at the Monteleone Hotel to discuss the preservation and beautification of the French Quarter, including the reconstruction of the French Opera House. (New Orleans States, February 1, 1920.)”

“The Commission Council of New Orleans establishes the first Vieux Carré Commission.”

“The American Institute of Architects, the National Parks Service, and the Library of Congress initiate the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) to document historic architecture.”

“The Works Progress Administration attempts to record and preserve the cultural history of Louisiana: its music, manuscripts, art, and buildings.”

“The Louisiana Legislature authorizes an amendment to the state’s Constitution to authorize the New Orleans City Council to create the Vieux Carré Commission (VCC).”

“Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents and Associates (VCPORA) incorporates with the mission of “preservation, restoration, beautification and general betterment of the Vieux Carré.””

A Catalyst for Preservation

Late in the evening of December 3, 1919, following a rehearsal of Carmen, the French Opera House caught fire. To this day the source of the blaze remains unknown.

Originally the building contained two lead-lined wooden reservoirs, each holding 3,500 gallons of water, with pipes that could be connected to hoses for fire protection. Whether or not an updated system had been installed since then, none of these provisions could save the building from destruction. Firefighters fought the blaze, but barely a shell remained.

Within months of the fire, French Quarter citizens and businesses, aware of a decline in the reputation of their neighborhood, at first vowed to rebuild the Opera House. That idea never came to fruition, but the year 1919 was a pivotal point in the history of New Orleans’s preservation movement. From 1921 to 1937 several groups formed to focus on beautification, restoration, and preservation of the Quarter. Such local groups as the Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents, and Associates (VCPORA) organized; the City Council created the Vieux Carré Commission to protect the neighborhood’s architectural and historic character; and national programs like the Works Progress Administration and the Historic American Buildings Survey brought attention to what historic buildings had been or could be lost without further action.

As Tulane University geographer and historian Richard Campanella has noted, “Preservationists need not be reminded of the power of old buildings. We recognize them as testaments of social memory, artifacts of architecture and vessels of culture, and we know all too well how their razing lays the groundwork for historical amnesia.” The destruction of the French Opera House building resulted not only in a physical void but a social one, leaving the city’s Creole populations without a central space for entertainment.

For almost forty years the lot at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse sat vacant, until 1965, when developers erected the five-story Downtowner Motor Inn. Today, the Four Points by Sheraton occupies the location.