Walking through a historic house museum staged in their original 19th century style, it is easy to get lost in the recreated grandeur of high society. However, if you look closely, every decorative aspect of the Hermann-Grima house is evidence of the grueling tasks that enslaved people living in New Orleans were forced to perform. To ensure their own comfort, enslavers delegated tasks that were dangerous, unsanitary, or unpleasant to domestic servants or enslaved people hired from other individuals or institutions. This includes cleaning to make the house look presentable, cooking and serving food to the family and their guests and even building the house itself.

Historically, the way museums have displayed decorative arts objects limit their interpretation to single-narrative stories. Curators and interpreters influence what is remembered about the creation, use, and ownership of objects and often paint only a partial picture. Intentionally focusing on “invisible labor” brings stories of erased populations to the forefront of the historical record of objects that cover up important labor with decorative elements.

This exhibit will examine ten decorative arts objects throughout the house to uncover the invisible labor performed by people enslaved by the Hermann and Grima families, as well as other wealthy families in pre-Civil War New Orleans.

Food service and production

Unknown, maker

Fleur-de-lis mold, France, circa 1830

Redware ceramic, 9 11/16 x 12 1/3 in.

Museum purchase, 1990.9.2

This redware cake mold is typical of ceramics produced in Alsace-Lorraine, France. Enslaved cooks like Sarah primarily used molds such as this one, and others in the pantry, during holidays to create decorative seasonal cakes. It was common for people of color in pre-Civil War New Orleans to create dishes from memory, not from written recipes, because of an 1830 law making it illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write. Forced illiteracy was another means of controlling enslaved people’s lives and robbing them of personal freedoms. Because of this, many cooking techniques enslaved cooks employed came from African traditions (mostly from the Senegambia region where many Louisiana enslaved people and their families originated) that had been passed down orally combined with French or Spanish influences dictated to them by the woman of the house, who could read them from a cookbook. The interplay of cuisines is so integral that many of the cookbooks already had influence from people of African descent. One example of this is The Woman’s Exchange’s own cookbook, Creole Cookery. Published in 1885 and widely understood to be one of the first New Orleans cookbooks, it acknowledged the influence of Creole cooks on Louisiana cooking.

[Figure 1. This redware cake mold resides in the Hermann-Grima pantry where various kitchen items could have been stored.]

Working in the open-hearth kitchen in extremely high temperatures, enslaved cooks handled cakes and other baked goods without modern oven-mitts while typically wearing long sleeves and skirts, putting them at high risk for burns.

[Figure 2. The beehive oven in the Hermann-Grima House’s open-hearth kitchen is where breads and cakes would have been baked, possibly in molds like the redware fleur-de-lys.]

The fleur-de-lis symbol is closely associated with France and, by extension, New Orleans; however, to a person enslaved in the city, it could remind them of their forced labor. Under French colonial rule, Louisiana’s Code Noir mandated that slaves who repeatedly attempted self-emancipation be branded with the fleur-de-lis to signal their runaway status to enslavers and potential buyers.

Although we do not have any record of branded slaves living at the St. Louis Street property, there are records of at least three enslaved people owned by the Hermanns who had either run away from the family or had a history of attempting self-emancipation from other situations. Samuel Hermann, Sr. purchased a 20-year-old woman named Betsey in 1829, and in the sale document, the seller mentioned that she had been “absent from his home once,” which is possibly why Hermann, Sr. sold her again just two months later.

Samuel Hermann, Jr. had purchased a man named Henry, aged 24, in 1828. In 1831, Hermann, Jr. posted two advertisements in the New Orleans Bee for Henry’s return with the promise of a $50 reward. After his inevitable capture, Hermann, Jr. sold him, describing him as “being in the habit of running away.” Finally, a man named Sam Cunningham who was purchased by Samuel Hermann, Jr in 1834, ran away and, upon his capture, was held in jail when an advertisement for his sale was published.

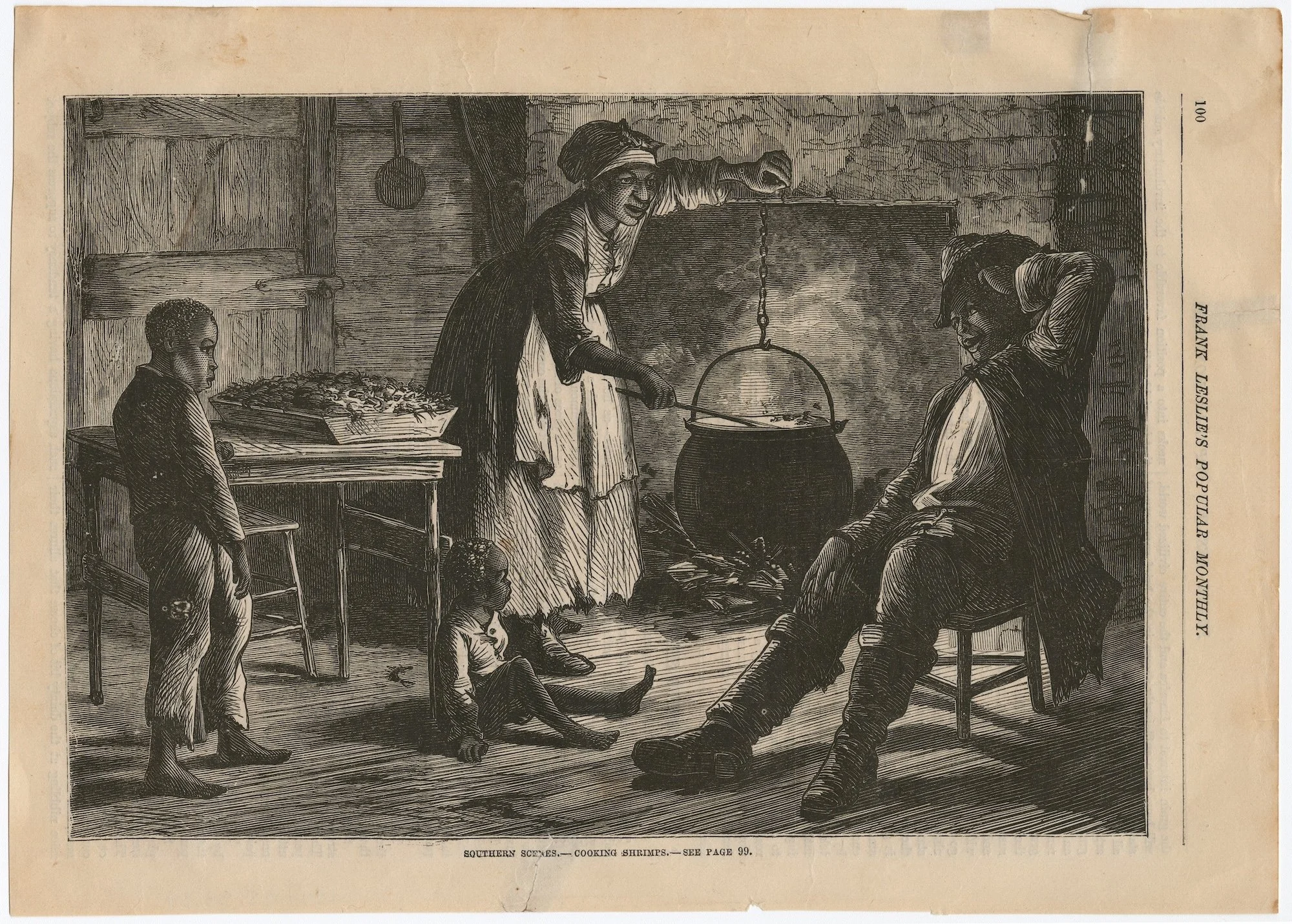

[Figure 3. This 1877 engraving shows a Black family in what seems to be their personal kitchen, with the woman stirring a large pot in a hearth. Although it was created later than the objects in the Hermann-Grima House, this illustration shows one possible way the open-hearth kitchen could have been used, and the title gives an idea of what might have been cooked. Historic New Orleans Collection, 1974.25.23.39.]

Unknown, maker

Dinner service

Paris, 1840-1850

Porcelain

Museum purchase, 1996.2.1-77

[Figure 4. Detail of a plate from the Hermann-Grima House dinner service. This is one of 77 pieces in the set.]

French culture was a dominant influence in 19th-century New Orleans, particularly in home and dining etiquettes. For meals in the dining room, enslaved domestic servants had to have special knowledge of the French manner of service. This Vieux Paris (“Old Paris”) dinner service dates to between 1840 and 1850. Old Paris porcelain, produced in small Paris factories, gained prominence among New Orleans buyers in the early 19th¹. Available in a variety of styles, shapes, and rich colors, it featured a solid color ground under painted decoration. This set includes several types of plates, a soup tureen, a fish platter, and soup bowls all decorated with a deep maroon border with gold accents. The large number of pieces in this set alludes to the popularity of the French dining style as well as the purchaser’s level of wealth because proper use of the array of pieces reflected the owners’ knowledge of property dining etiquette.

[Figure 5. Image of a vegetable dish with pomegranate fruit and leaf decoration on lid from the Hermann-Grima House dinner service.]

Enslaved domestic servants, including cooks and waiters, handled most of a meal’s logistics. They were expected to carefully navigate the crowded dining room with hot, delicate plates, know where and when to place the plates, and present dishes to guests in a choreographed effort that made them both necessary and practically invisible². After meals, enslaved people washed and dried the dishes in the scullery, a room adjacent to the open-hearth kitchen that was dedicated to this task.

In dishwashing, some enslaved people found a small means of resistance. Chipping even a single dish would reduce the value of the entire dinner service, and knowledge of this consequence could be empowering. If one intentionally damaged a dish and was perceived as clumsy, they could be denied access to the home’s valuable dinnerware. As a result, in some casesthe woman of the house took over the washing of the most delicate pieces—one less task assigned to the overworked servant.

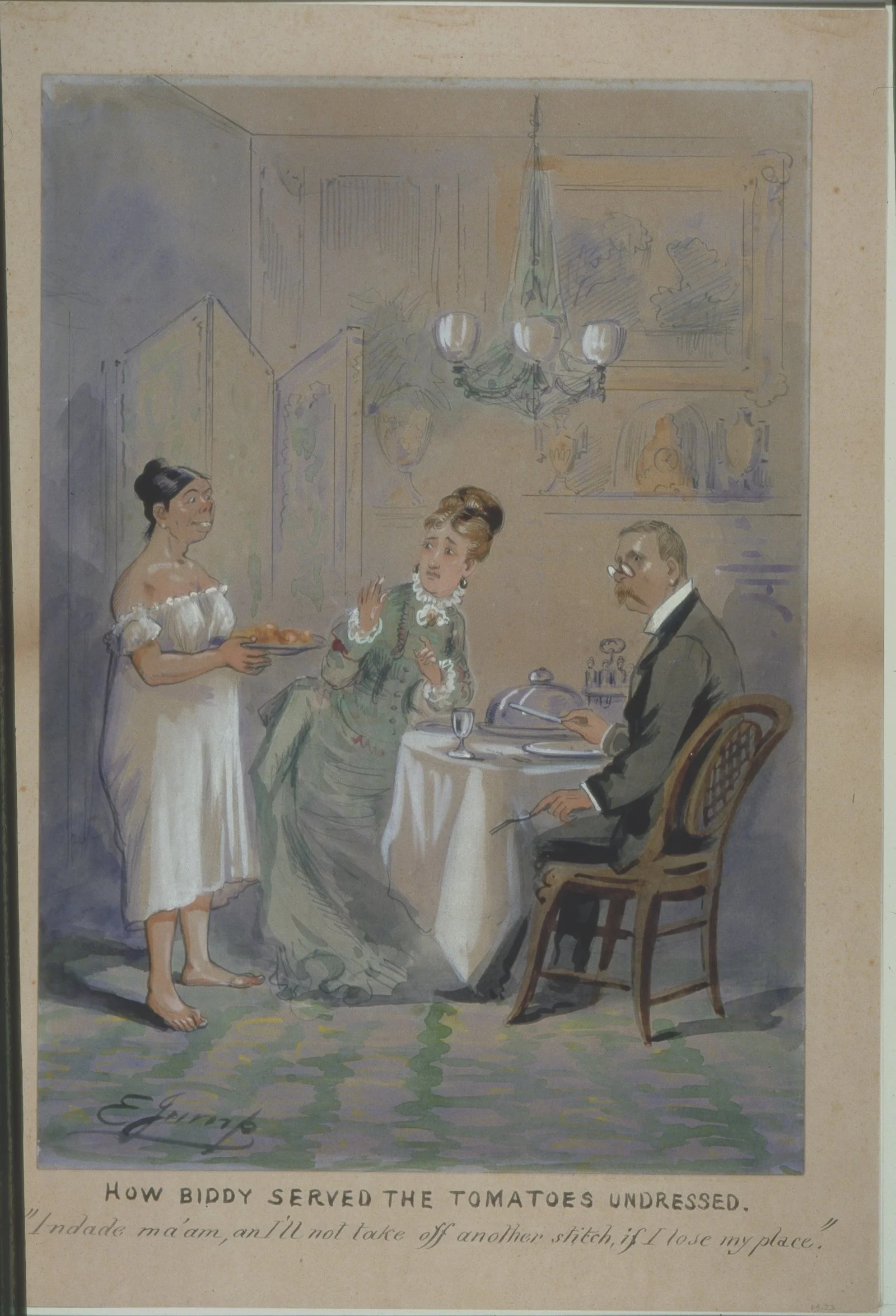

[Figure 6. Watercolor illustration with the title “How Biddy Served the Tomatoes Undressed,” created in 1878. This sketch was intended to comedically comment on the fact that many enslaved people were uneducated or otherwise “backwards” in their manners, including style of speech, which is mocked in the caption. Despite this, enslaved persons were expected to know the intricacies of serving and cooking in the French fashion. Historic New Orleans Collection. The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1949.23.]

Unknown, maker

Plate Warmer, United States or United Kingdom, 1840

Tole

Gift of Mrs. Beauregard Bassich, 1983.5

[Figure 7. Plate warmer with door open to show open back and inside shelves.]

Placing this appliance close to a fire brought the temperature high enough that it was essentially a small oven. Enslaved individuals placed porcelain plates (hard enough to withstand extreme heat) onto the internal shelves to keep them warm, so that the white hosts and their guests would be served food at the optimal temperature. While those at the table probably took this luxury for granted, the enslaved individuals would have to face burning temperatures at every meal. The many courses served meant multiple rounds of plates would need warming. The enslaved individuals would have to serve the food on time, clear the table between courses, and sometimes travel between the outside kitchen and the pantry to plate the food, all while risking their own physical safety in close proximity to open flames and expensive, breakable furnishings.

[Figure 8. Plate warmer in context in front of Hermann-Grima House fireplace.]

Records show at least six people enslaved by the Hermanns or Grimas who served as cooks and therefore interacted with objects like these. A boy named Oliver was purchased by Samuel Hermann, Jr. in 1830 along with his—probably twin—brother, both aged 14 years. He was sold 13 years later as a cook. In 1831, Samuel Hermann, Sr. purchased a girl named Charlotte, sometimes called Doreus, who was 17 years old and a “good ironer and cook in the French tradition.” A woman named Sarah was purchased by Samuell Hermann Sr. in 1832 when she was 27 years old. She lived in the Hermanns for 19 years before she was sold in 1851 as a cook, aged about 46 years. Samuel Hermann, Jr. purchased a man named Adolphe in 1836 who the seller described as “a certain negro boy…aged about twenty-seven years, a good cook.” Felix Grima purchased an 18-year-old woman named Eliza in 1833, who was a laundress and a cook. In 1850, he purchased a man who was about 36 years old, and a coach driver, house servant, and cook. Some of these workers may have also served food to the Hermanns, Grimas, and guests if they also had the skills and knowledge of domestic servants.

[Figure 9. This pencil sketch by Alfred Rudolph Waud was likely drawn in New Orleans between 1860 and 1869. It shows what an African American woman employed as a cook at this time might have worn, including what seems to be a tignon (head wrap) and apron tied around her waist. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.]

Entertaining Spaces

Unknown, maker

Girandoles, United States, circa 1840

Metal, glass, and marble

Museum purchase, 1983.6.1-3

Figural girandoles such as these were a uniquely American decorative object, originating in their common form around the 1840s³. Girandoles were pricier than plain tin candlesticks, making them a status symbol for those who could afford them, but they still cost less than bigger fixtures such as lamps, so they became accessible to middle-class laborers if they saved up a few weeks’ pay. The heavy marble base and sparkling crystal prisms added to the luxurious appearance, and girandoles came to be used primarily as mantle decoration rather than functional fixtures.

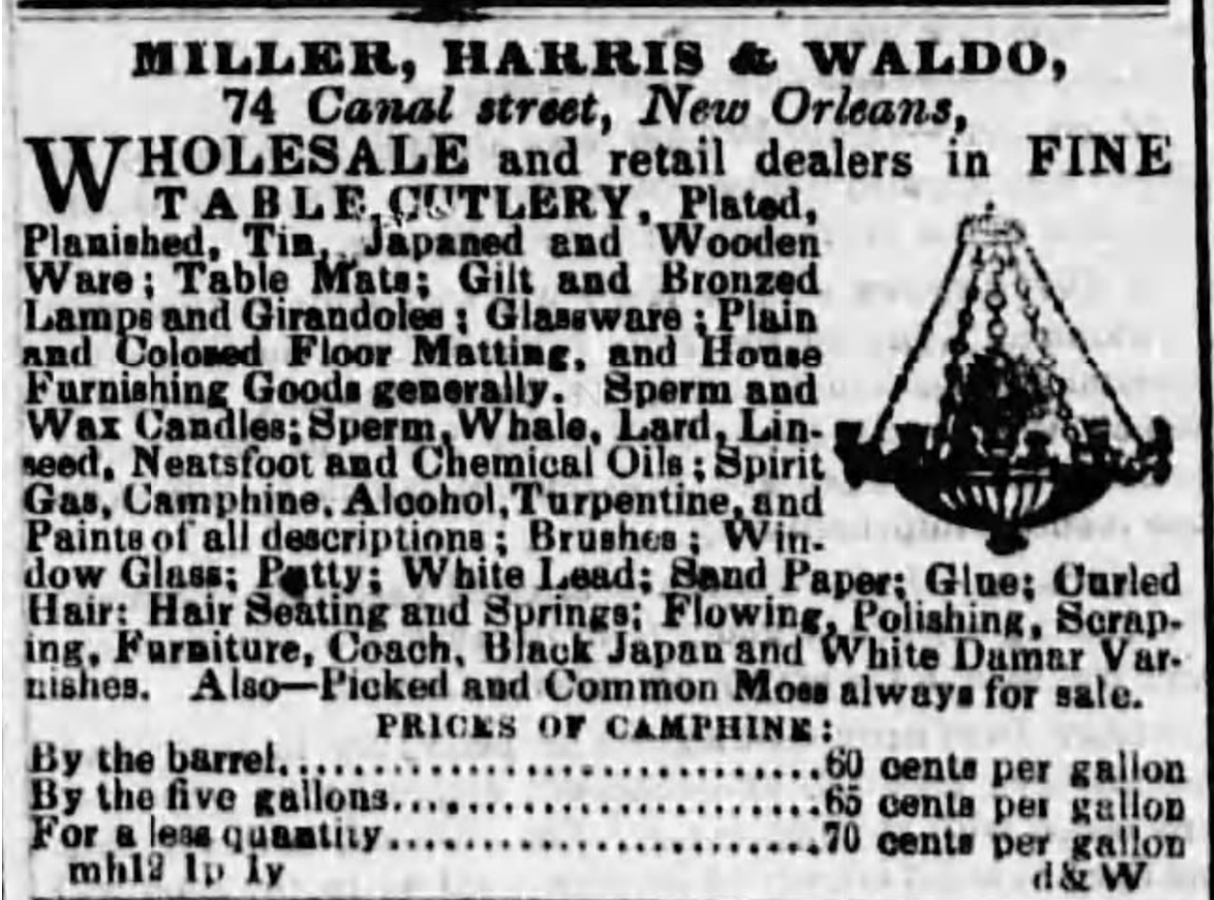

[Figure 10. Advertisement for Miller, Harris & Waldo for various household furnishings, including girandoles and candles of various materials in The New Orleans Crescent from Tuesday, November 18, 1851.]

The delicately connected prisms made cleaning complicated since they often fell off and were expensive to replace. This would have made the job of cleaning the mantle extra tedious for enslaved domestic servants. Not only did they risk breaking the girandoles or scratching the crystal if they used the wrong cleaning material on it, but they also risked ridicule and punishment for any mistakes they made during the process.

[Figure 11. Girandole set from the Hermann-Grima House.]

[Figure 12. Detail of Hermann-Grima House girandole set depicting two children under a tree playing with a lamb.]

Lighting the candles in the girandoles, or in any light fixture at the time, also posed a risk to the safety of enslaved people, who had to take extra care not to burn themselves or any fabrics, such as curtains, tablecloths, or their own clothing. Once candles were lit, they would also be responsible for monitoring them to prevent housefires, replace candles, and keep children away from the flames.

[Figure 13. Girandole set on the mantle of the Hermann-Grima House dining room.]

Additionally, the detailed figural decorations on these girandoles and others like them typically were taken from literature and meant to reflect the owner’s learnedness and high morality. Bible scenes and “oriental” figures proliferated. The increase in global trade led to a fascination with the “orient,” or Eastern world, during the 18th and 19th centuries. By owning and displaying decor with imagery such as these, homeowners reflected their knowledge of biblical stories, literature, and global cultures, projecting a well-educated image to guests. Even though enslaved people cleaned them, forced illiteracy and divergent lived experiences inhibited their understanding of the objects’ cultural significance.

Unknown, maker

Hurricane Shades, United States, 1850-1865

Glass, 21 ½ in

Gift of Grima Johnson family, 2003.44.4A/B

This pair of delicately engraved glass hurricane shades, sometimes called “smoke shades” or “hurricane glasses”, were placed over candles and candlesticks on the table to protect the flame from being extinguished and sleeves, napkins, or tablecloths from getting burned⁴. Over time, smoke from the lit candles beneath would collect on the inside surface of the glass, which would require regular cleaning.

[Figure 14. Hurricane shade from Hermann-Grima House.]

Because the shades are so delicate and expensive, lifting and cleaning them would have been a difficult but important task. Fingerprints are easily visible on the glass, so the shades likely were cleaned after each handling. Scratches or chips significantly lowered the value of the shades, made them less resistant to breakage and reflected poorly on their owner. Any slight slip during cleaning or moving could result in dropping and shattering the shade, not only destroying one but rendering the surviving shade less valuable.

[Figure 15. Detail of Hermann-Grima House hurricane shade showing hand-etched leaf design.]

[Figure 16. Hermann-Grima House dining table with hurricane shades positioned as they would have been during a meal, over candlesticks.]

Unknown, maker

Highchair, United States, circa 1840

Mahogany, horsehair, brass, 25 x 15 x 11 1/2 in.

Gift of Mrs. F. Evans Farwell, 1979.1.7a-d

This child-sized highchair is made of mahogany, one of the most prized woods in nineteenth-century Louisiana for its high shine, naturally appealing grain pattern, and durability. The wood was native to South Africa and mainly cultivated in the West Indies on mahogany plantations.

[Figure 17. Highchair with separate table and chair components from the Hermann-Grima House children’s bedroom.]

[Figure 18. Hermann-Grima House highchair separated into chair and table components. Also visible in the adjustable footrest mechanism and removable arm bar.]

Many wealthy families owned enslaved nurses who tended to the physical and emotional needs of the children of their enslavers. Some, called “wet-nurses,” fed the white children of their enslavers from their own breast. To have the ability to nurse, the women would either have a young child of their own still under their care or have given birth recently to a child who either died within a few days, whom they had been forced to abandon, or who was forcefully taken from them. According to Louisiana’s 1724 Code Noir, prepubescent children (enfans impubères) were not allowed to be sold apart from their mothers, although this was likely loosely enforced. If the enslaved women were able to keep their children, they would often grow up alongside the white children until they were able to perform work around the house.

As childcare providers, enslaved nurses would be expected to feed, bathe, and keep the children under their care safe, raising them until adulthood. Oftentimes the children they raised grew up to be their legal enslavers.

[Figure 19. Butler children and nurse, oil on canvas, painted in New Orleans between 1830 and 1850, depicts a Black, likely enslaved, female nurse with two white children from the Butler family. Nurses like this woman served wealthy families in New Orleans and would have been the ones to feed, bathe, and clothe children. An enslaved nurse presumably was the primary user of the Hermann-Grima House highchair. Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Mrs. Virginia Bruns Marshall, 2017.0271.4.]

[Figure 20. Wood engraving with the caption “Nurse—Old Style.” Printed around 1873, it shows a side profile of an African American woman with a large, tall headwrap and a striped shawl, perhaps similar to the accessories worn by nurses caring for the Hermann and Grima children.]

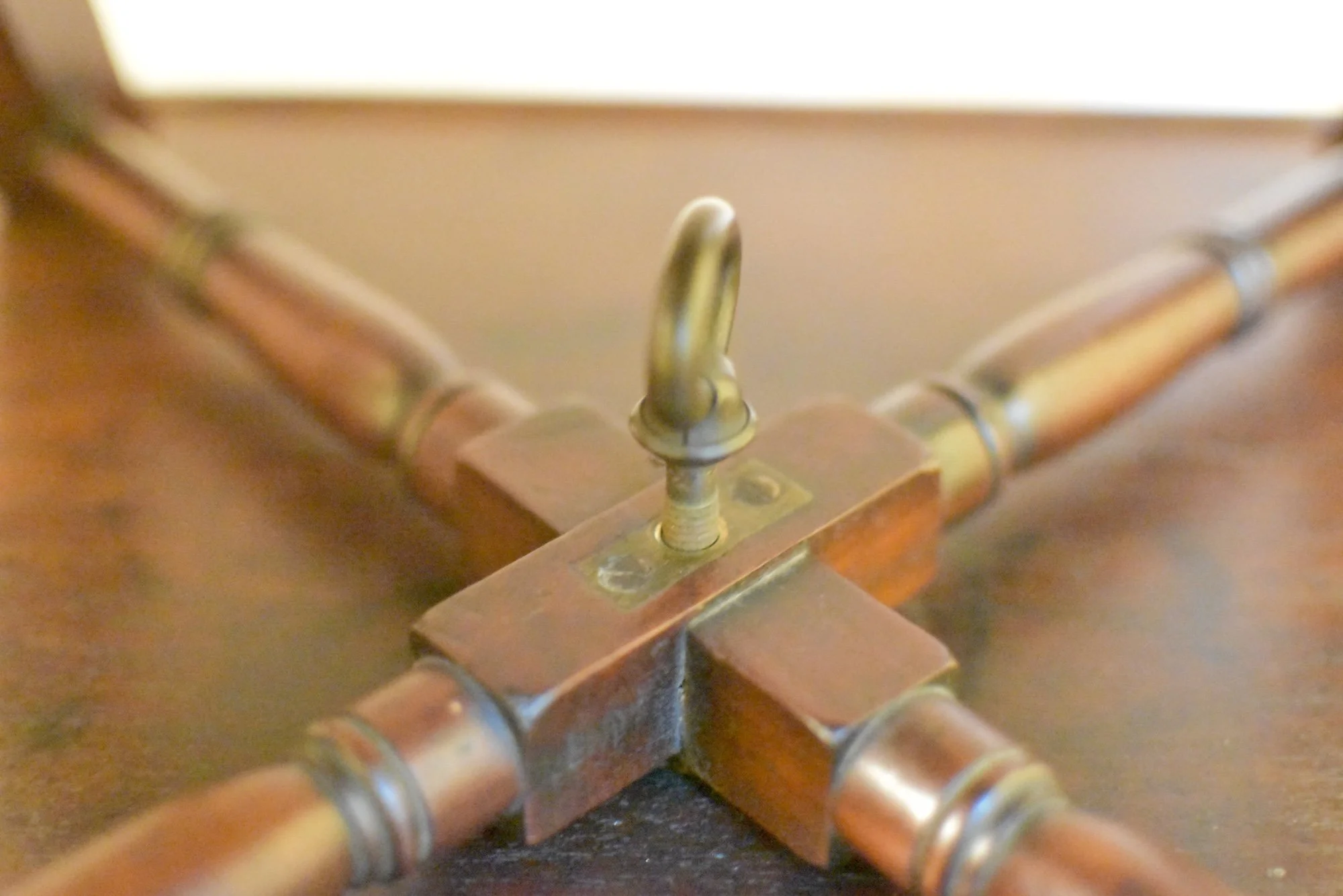

A brass screw connects the x-shaped stretcher supporting the chair to another element, which, when separated, serves as a small table to be used with the (now shorter) chair. Like the specialized knowledge of enslaved waiters serving an elaborate meal, an awareness of the mechanisms of this convertible chair was required for its use by an enslaved person. Each instance of its use—especially before one was familiar—could be another source of anxiety for a laborer and damaging it could result in punishment.

Without extant records identifying a wet-nurse at the Hermann-Grima House, it is difficult to say who may have nursed the Hermann and Grima children. However, the records of women purchased with children under a year old in the house are extensive. A woman named Maria was purchased in 1821 with her six-week-old son, James. Maria would have been the proper age to be a wet nurse when Samuel Hermann (?) purchased her, and, since the pair lived with the Hermanns for 17 years, James would likely have grown up around the Hermann children. The Grimas also purchased a woman named Sally and her 3-month-old son, as well as Justine and her two daughters, one six years old and one only a few months old.

[Figure 21. An engraving of a painting by Basile de Loose titled 'Family in an Interior,’ featuring a woman sewing with three children around her. The child on the right is seated in a highchair similar to the Hermann-Grima House example. Courtesy of The Getty Museum.]

Carved frieze

circa 1831

Wood (probably pine), paint*

This elaborately carved frieze above a set of pocket doors (or “sliding-doors”, as 19th-century architects called them) dividing the Hermann-Grima House parlor and dining room is flanked by two Corinthian columns. While the frieze looks like marble, it is in fact painted, carved wood.

[Figure 22. Image of Hermann-Grima frieze on dining room side.]

On the parlor side of the frieze, between the two Corinthian column capitals, elaborate drapery, adorned with blooming flowers and hanging from tasseled ropes, is carved into the wood. At the very center is a basket full of fruits, vegetables, and greenery out of which twisting vines stretch towards the columns. On the dining room side, the fruit basket is mirrored without the twisting vines. To either side sits a cornucopia overflowing with various crops and greenery. Replacing the drapery are flower-covered garlands connecting large flowers.

The details of the sumptuously designed frieze and the fluted Corinthian columns that frame it were not outlined in the original 1831 building contract for the house between builder William Brand and Samuel Hermann; they likely were added on at some point during the building process or contained in a separate contract, which the museum’s research has not yet produced.

[Figure 23. Architectural illustration, published in 1830, of a design for sliding-doors, Corinthian columns, and a blank frieze from Boston’s Tremont House. The composition bears a striking resemblance to Hermann-Grima House’s example. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.]

That group included the following carpenters:

Solomon, very good carpenter, aged 34 years, 8 years in the country, excellent character

George, first rate carpenter, aged 21 years, 9 years in the country, most excellent character

John Sprague, good carpenter, aged 20 years, 5 years in the country, he absented himself twice from work, not longer than a day or two, but returned of his own accord, otherwise a good character

William Thomas, rough carpenter, aged 17 years, 10 years in the country, first rate boy

John Johnson, rough carpenter, aged 21 years, 3 years in the country, very good character, has had a breaking out under his jaws, but will be perfectly cured

In a similar advertisement for bricklayers, Brand noted they were “some of the best” and able to “build from a plan”, so one would expect the same level of skill from the carpenters working for him.

*Material analysis of the frieze is forthcoming to confirm the composition and wood type.

Bedroom

Unknown, maker

Bathtub, United States, circa 1860

Zinc-plated iron

Museum purchase, 1990.1

This clawfoot tub was used by the white homeowners and their children. Because there was no running water, enslaved workers filled the tub with buckets of water they hauled in from the cistern that collected rainwater at the far end of the courtyard. For a warm bath, they also had to heat the water over a fire in the hearth or scullery, adding the danger of being burned to the physically straining process of filling up a tub by bucket. To empty it, enslaved workers lifted the tub off the detachable feet and poured the water out the side doors of the bathroom, where it would then run along the French drain into the street. This bathtub, bathroom, and the bathwater would likely have been shared by all members of family, who would have bathed only every few days, and rarely more than once a week.

[Figure 24. Bathtub in the bathroom behind the children’s room in the Hermann-Grima House. A cloth may have been draped over the inside as seen here to make sitting on the metal more comfortable.]

Enslaved people themselves were not allowed to use this tub but rather bathed in smaller, portable tubs. These small tubs were likely used outside or in courtyards to avoid water damage to the floors in slave quarters.

[Figure 25. Detail of clawfoot frame on which the tub sits.]

Unknown, maker

Veilleuse, France, circa 1835

Porcelain, 10 x 4 1/4 in

1974.10.1_A-D

This small object would have held tea or medicine in the top teapot and a small candle in the cylinder at the bottom to keep the liquid warm. It is called a veilleuse, which means “night light”, or tisannière which refers to the tisane, or tea, that would be held in it. The dim light from the candle would also have provided enough visibility for minor activities people might have had to do at night without having to light a larger candlestick.

[Figure 26. Veilleuse previously owned by Eugenie Debuys, Sameul Hermann, Jr.’s wife.]

Kept at the bedside, veilleuses were handled personally by the owners of the house more than other publicly used dishware, but the water that was boiled for the tea and any herbs that were collected for medicines likely was gathered and prepared by the enslaved domestic servants. Some wealthy families like the Hermanns and Grimas bought bottled water, but likely still required enslaved domestic servants to boil it for cooking and consumption in teas and medicines.

This veilleuse was owned by Eugenie Dubuys, who married Samuel Hermann Jr. in 1835. She likely used it at her bedside at 173 Customhouse Street where the couple moved after marriage⁵. Dubuys’ veilleuse is an example of Old Paris porcelain, which was popular among New Orleans French Creoles and other European-descended elites.

[Figure 27. Veilleuse separated into component parts to display how the appliance was used. The tall cylindrical piece would sit around a tea candle that fits into the short, round base. The small teapot would then be placed atop the cylinder to keep the contents warm.]

Samuel Hermann Jr purchased a woman named Mary or Mariah shortly after his marriage to Eugenie Dubuys in 1835. She was described as "a quartroon (sic), about 14 years, speaks French and English, has been in the country from infancy.” She lived with the family for eight months and was sold as a seamstress, child nurse, and house servant. It is possible she assisted Eugenie with preparing her medicinal tisanes.

Unknown, maker

Bed steps with Chamber Pot, England, 1830

Mahogony, 26 x 18 in

Museum purchase, 2005.1

The main function of bed steps was to help 19th century people get into raised beds. However, Hermann-Grima House’s example served another hidden purpose: the middle step also opens to reveal a large circular hole that would have held a chamber pot. It could also have been used for someone with health or mobility issues, especially in old age, as having a commode so close to the bed would have made relieving oneself faster and easier. The top step also conceals a small compartment that could be used for storage, perhaps for a cloth for users to dry themselves after cleaning up in the wash basin after using the chamber pot.

[Figure 28. Bed steps located next to the bed in the main bedroom of the Hermann-Grima House. The middle step pulls out to reveal a large hole in which a chamber pot would have been kept. The top step opens to become a small storage area.]

Although the steps made life for the homeowners more convenient, the enslaved workers had the unpleasant job of emptying and cleaning the chamber pot inside. This work was sometimes done by enslaved children. If this set of bed steps was used in the main bedroom of the Hermann-Grima House, which is on the second floor, a good deal of labor was involved: someone had to bring the chamber pot up and down the steep service stairs, deposit the waste into a pit outside or set it aside for use as garden fertilizer, clean the pot (likely with water gathered from the cistern), and replace it in the room to be reused.

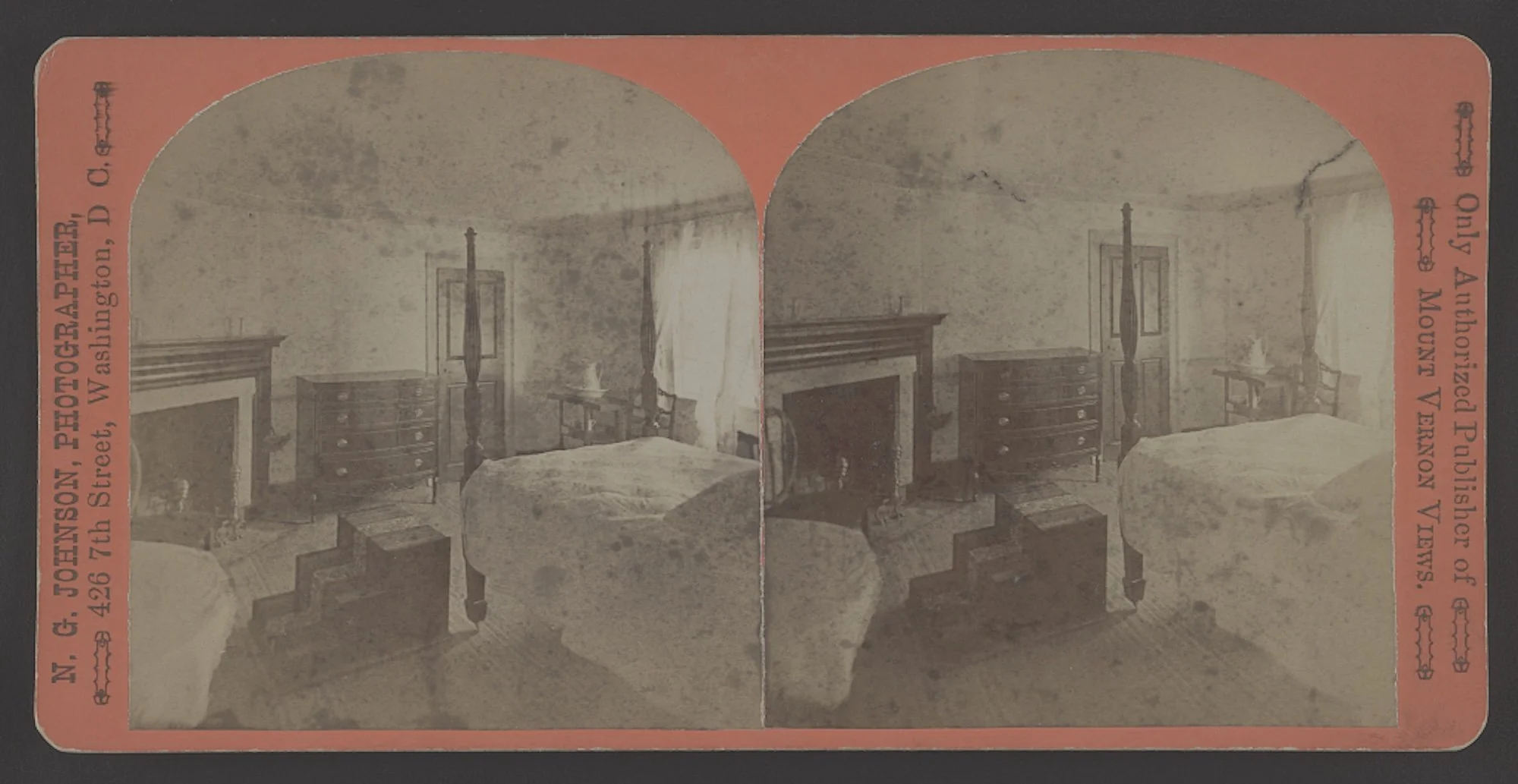

[Figure 29. Photograph of the Maryland Room at Mount Vernon, where Eleanor Curtis, George Washington’s adopted daughter, stayed. The bed steps that she used, which are similar to the ones at the Hermann-Grima House, can be seen next to her bed in the photo. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.]

¹ Rebus Inc. New Orleans Porcelain. Knapp Press, 1984.

² Roberts, Robert. The House Servant’s Directory. Boston: Munroe & Francis, 1827.

³ Ulysses G. Dietz. Victorian Lighting: The Dietz Catalogue of 1860, With a new history of Dietz & Victorian Lighting. Watkins Glen, NY: The American Life Foundation, 1982

⁴ Darbee, Herbert C. “A GLOSSARY OF OLD LAMPS: And Lighting Devices.” History News 20, no. 8 (1965): 159–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42651280.

⁵ Samuel Hermann Jr. and Eugenie DeBuys lived at 173 Customhouse Street, according to the 1842 New Orleans City Directory.